Defence Secretary John Healey hailed the government’s defence review as the “first of its kind” and said it will “take a fresh look at the challenges we face”.

Mr Healey noted the “increasing instability and uncertainty” around the world, including the conflict in the Middle East and war in Ukraine, and said “threats are growing”.

The strategic defence review will consider the current state of the armed forces, the threats the UK faces and the capabilities needed to address them.

Sir Keir Starmer has previously said the review will set out a “roadmap” to the goal of spending 2.5% of national income on defence – a target he has made a “cast iron” commitment to but is yet to put a timeline on.

On Monday, the prime minister said the “root and branch review” of the armed forces would help prepare the UK for “a more dangerous and volatile world”.

The review will invite submissions from the military, veterans, MPs, the defence industry, the public, academics and the UK’s allies until the end of September and aims to deliver its findings in the first half of 2025.

“I promised the British people I would deliver the change needed to take our country forward, and I promised action not words,” Sir Keir said.

“That’s why one of my first acts since taking office is to launch our strategic defence review.

“We will make sure our hollowed out armed forces are bolstered and respected, that defence spending is responsibly increased, and that our country has the capabilities needed to ensure the UK’s resilience for the long term.”

The review will be overseen by Defence Secretary John Healey and headed by former Nato Secretary General Lord Robertson along with former US presidential advisor Fiona Hill and former Joint Force Commander Gen Sir Richard Barrons.

The group will have their work cut out.

The global security threats facing the UK and its Western allies are more serious and more complex than at any time since the end of the Cold War in 1990.

They also coincide with what many commentators have said is a catastrophic running down of the UK’s armed forces to the point where the country is arguably no longer considered to be a Tier One military force.

In terms of the number of troops in its regular forces, the British Army is now at its smallest size since the time of the Napoleonic Wars two centuries ago.

Recruitment is failing to match retention, with many soldiers and officers complaining about neglected and substandard accommodation.

The Royal Navy, which has spent vast sums on its two centrepiece aircraft carriers, is in need of many more surface ships to fulfil its tasks around the globe.

Its ageing fleet of nuclear-armed Vanguard submarines, the cornerstone of the UK’s strategic defence and known as the Continuous At Sea Deterrent (CASD), is overdue for replacement by four Dreadnought class submarines and costs are mounting.

Commenting on the review, Mr Healey said: “Hollowed-out armed forces, procurement waste and neglected morale cannot continue.”

Too many UK commitments?

The defence and security threats facing the UK, Nato and its allies further afield are multiple.

They include a war raging on Europe’s eastern flank in Ukraine against Russia’s full-scale invasion. The UK, along with the EU and Nato, has opted to help defend Ukraine with multi-billion pound packages of weapons and aid, stopping short of committing combat troops.

The policy behind this is not entirely altruistic. European governments, especially those closest to Russia like Poland and the Baltic states, fear that if President Putin wins the war in Ukraine it will not be long before he rebuilds his army and invades them next.

Some of those countries are already busy beefing up their own defence spending closer to 3% or even 4% of GDP.

The challenge for Nato has been how to provide Ukraine with as much weaponry as it can, without provoking Russia into retaliating against a Nato state and risk triggering a third world war.

The Royal Navy has been in action recently in the Red Sea, where it has been operating alongside the US Navy in fending off attacks on shipping by the Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen.

But the UK has also made naval commitments further afield in the South China Sea with the Aukus pact, comprising of Australia, UK and the US, aimed at containing Chinese expansion in the region.

Critics have questioned whether a financially-constrained UK can afford to make commitments like this on the other side of the world.

Closer to home in Europe, there is a growing threat from so-called “hybrid warfare” attacks, suspected of coming from Russia.

These are anonymous, unattributable attacks on undersea pipelines and telecoms cables on which Western nations depend.

As tensions increase with Moscow there are fears such actions will only increase and the UK cannot possibly hope to guard all of its coastline all of the time.

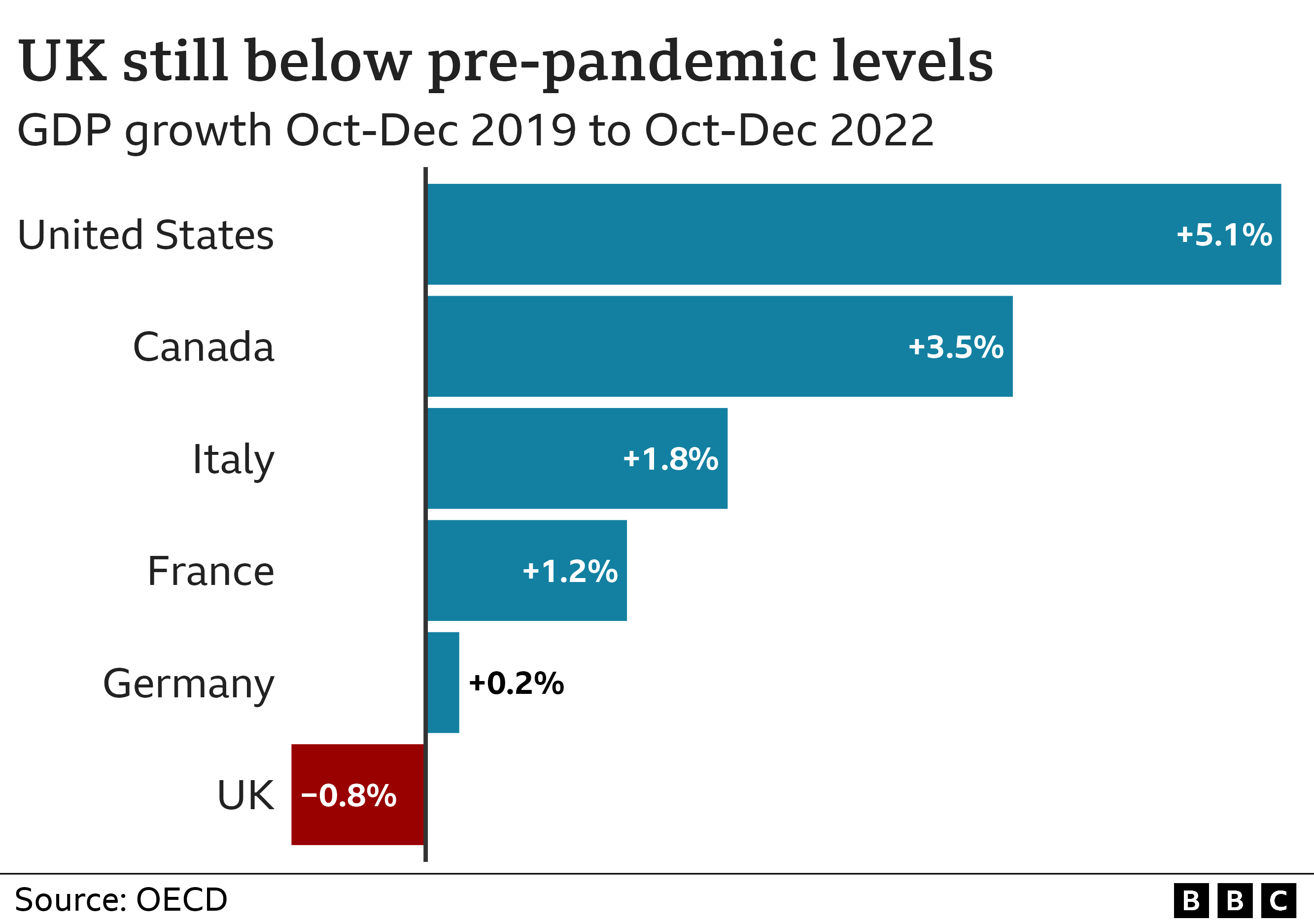

But while those nervous Nato partners living close to Russia’s borders are busy beefing up their defence spending closer to 3 or even 4% of GDP, the UK has so far declined to put a timetable on when it will raise its own defence spending to just 2.5%.

Opposition figures have criticised the government for refusing to say when defence spending will be increased.

Before his election defeat, former prime minister Rishi Sunak committed to reaching 2.5% by 2030.

Shadow defence secretary James Cartlidge previously said: “In a world that is more volatile and dangerous than at any time since the Cold War, Keir Starmer’s Labour government had a clear choice to match the Conservatives’ fully funded pledge to spend 2.5% of GDP on defence by 2030.

“By failing to do so, they’ve created huge uncertainty for our armed forces, at the worst possible time.”

Reports /Trainviral/

Fashion2 years ago

Fashion2 years ago

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years ago

Everything About Youtube2 years ago

Everything About Youtube2 years ago

Fashion2 years ago

Fashion2 years ago

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years ago

Everything About Youtube2 years ago

Everything About Youtube2 years ago

Tech2 years ago

Tech2 years ago